Information Through the Ages

Photo Credit: janGlas

Let me ask you three questions:

1. Who is the current president of France?

2. What is the effect of altitude on the boiling temperature of water?

3. Which organ is malfunctioning when the whites of your eyes become jaundice?

These questions encompass three central necessities of information and knowledge: current events, scientific discovery, and personal health. In this post, we’ll take a look back in history to see how such questions may have been answered in several distinct time periods

Age of the Scribe (2,000 BC – 15th Century AD)

Before the advent of the printing press, every page of text had to be written by hand. Think about that for a second: every word of every book had to be physically etched out by a scribe. The sheer labor of this this process, not to mention the skill and technique involved in producing legible reproductions, is immeasurable. In the age of the scribe, only the wealthy could afford the cost of accessing knowledge. Commoners had limited library resources and were largely helpless in building on previous pillars of discovery. It is impossible to infer about natural phenomena if the whole picture, as it’s known at that time, is not laid out in front of you.

News of worldwide events was slow to spread, so our notion of “current” is a relatively recent one. Take the first question for example. If you knew the president of France off the top of your head, I commend you. If not, I want you to consider how many people you would have to physically interact with in order to get an answer. Even if someone gave you an answer, how much longer would it take for you to ensure its veracity? There is something to be said about getting the facts in writing, and from a respectable source.

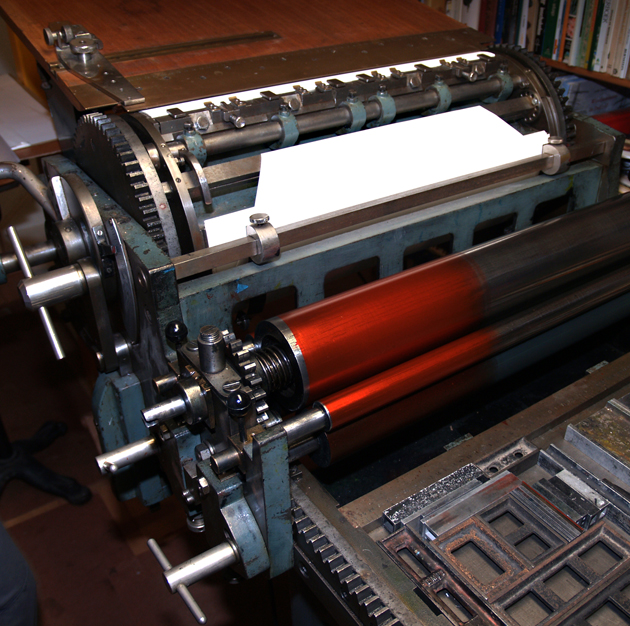

Age of the Printing Press (15th Century – 1990s)

Although the invention of the printing press is attributed to Bi Sheng, a Hans Chinese printer, the massive literary and scientific explosion occurred after German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg patented his version of the press. For the first time in European history, books of all disciplines could be produced and circulated by the thousands. The cost of information dropped sharply, giving access to individuals who were previously forced to survive on the bare outskirts of knowledge. Scientists could now hold discussions about modern experiments on a level playing field and they could build on formulas accurately recorded and massively reproduced. The best journals and novels were circulated the heaviest, and a canon of literature and science began to materialize. Medical observations were compiled and popularized leading to more doctors with accurate tools for diagnoses.

Internet Age (1990s – Present)

I found the answer to all three questions in exactly 29 seconds. Eighteenth century scholars could never have imagined the rate at which we access information today. We are empowered and spoiled by the ease of communicating ideas and the swiftness of learning new things. In the era of Googling, no academic knowledge is excluded from the masses. Top quality education is offered for free and the data hosted on the Internet grows exponentially year-by-year. If we’ve reached an informational utopia, then what’s stopping all our students from exceeding the academic levels of their 20th century counterparts? Could there be such thing as too much information?

Apparently, there is. Information overload, according to McKinsey Quarterly, results in attention fragmentation, particularly when it comes to organizing the mass amount of data at our disposal. Multitasking hurts our creativity, slashes efficiency, and releases chemicals associated with addiction, so we love to love it. What the research really shows us is that having too much of a good thing can genuinely hurt us.

I’ll leave you with a saying my close Greek friend lives by every day: “Παν μέτρον άριστον” (pan metron ariston). See how long it takes you to translate its meaning.

No comments